I know many of you are wondering what the upcoming winter will bring. I am actively working on my long range winter outlook but it will be a bit before I have everything compiled. In the meantime, a lot of folks are looking at other methods for telling what the weather will be like.

There are a lot of things people use such as persimmon seeds, wooly bear caterpillars, the  number of fogs in August, just to name a few. While many of us in the 21st century may think weather lore is more whimsical that wise, it’s hard to discount all of these “natural forecasters,” especially when they prove to be true. But how could a saying that’s been passed down from sailor to farmer to business executive really predict the weather?

number of fogs in August, just to name a few. While many of us in the 21st century may think weather lore is more whimsical that wise, it’s hard to discount all of these “natural forecasters,” especially when they prove to be true. But how could a saying that’s been passed down from sailor to farmer to business executive really predict the weather?

While not all weather lore is accurate, there are many sayings that prove to be on the mark time and time again. When you examine weather lore, you realize that the basics of this weather predicting method are careful observations that have been made over many years. Weather lore relies on the notion that there is a strong cause-and-effect relationship between nature and the weather. A weather lore forecaster takes cues from nature at the time he or she needs to know what the weather is going to be like. It is more of a short-term forecast for a specific area, rather than a long-term forecast for broad areas.  Can the amount of fog we see in August be used to predict snowfall in the winter? According to weather folklore, (and a couple of my coworkers), it can. “For every foggy morning in August, it will snow that many days in winter.” It seems like this would be something simple to keep track of, but like many of the old weather proverbs you find, it won’t work for all times and places.

Can the amount of fog we see in August be used to predict snowfall in the winter? According to weather folklore, (and a couple of my coworkers), it can. “For every foggy morning in August, it will snow that many days in winter.” It seems like this would be something simple to keep track of, but like many of the old weather proverbs you find, it won’t work for all times and places.

You will see fog in the Mississippi River bottom in August, but it doesn’t always extend to the higher hills outside of the floodplain. Why would we want to count the number of fogs anyway? The Missouri Folklore Society says that predictions like these help us cope with the uncertainty of the future. What about the accuracy? In a recent winter, the Cape Girardeau Missouri Airport reported they had snow or flurries on 28 days and fog was reported 29 times that August. Interesting, but I don’t think it would be accurate all of the time.

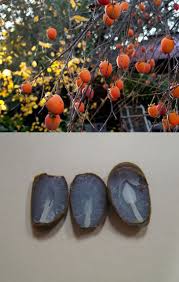

Weather lore is the distilled essence of ten thousand years of weather watching by cultures all over the world. And while these weather rules were made without the benefit of science many have a sound scientific basis which just goes to show that our ancestors weren’t stupid. But can wooly worms and persimmon seeds predict winter weather? According to  weather folklore, you can predict winter weather with a persimmon seed. Here’s how to do it: Persimmons are small orange fruits the size of a plum. The fruits may be sold anywhere, but the trees usually grow in zones 6 or warmer. Cut open a persimmon seed. It should be locally-grown to reflect your weather.

weather folklore, you can predict winter weather with a persimmon seed. Here’s how to do it: Persimmons are small orange fruits the size of a plum. The fruits may be sold anywhere, but the trees usually grow in zones 6 or warmer. Cut open a persimmon seed. It should be locally-grown to reflect your weather.

The folklore behind the persimmon seed is that when you split the seed open, you’ll find one of three shapes: a spoon, knife and a fork. A spoon means heavy, wet snow; a knife means cold, cutting winds; and a fork means a mild and tolerable winter. Unfortunately, there’s no science to back any of this up. If you look at this closer, you’ll find persimmon trees that have fruits with seeds of varying shapes on the same tree, the same year. Also, the spoon in the predominant, most commonly found shape so those two facts kind of take away from the true accuracy of this.

Woolly worms are another creature tied to winter weather forecasting folklore. The blacker the worm, the harsher the winter and the browner the worm, the milder the winter. But is there any scientific merit to the legend? In the fall of 1948, according to The Old Farmer’s Almanac, C. H. Curran, curator of insects at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, decided to put that claim to the test.  Between 1948 and 1956, he conducted experiments on woolly bears in which he found that the brown bands took up more than a third of the woolly bear’s body. The corresponding winters were milder than average, and Curran concluded that the folklore has some merit. However, according to the Almanac, he realized that his samples were small and saw his experiments as an excuse for having fun.

Between 1948 and 1956, he conducted experiments on woolly bears in which he found that the brown bands took up more than a third of the woolly bear’s body. The corresponding winters were milder than average, and Curran concluded that the folklore has some merit. However, according to the Almanac, he realized that his samples were small and saw his experiments as an excuse for having fun.

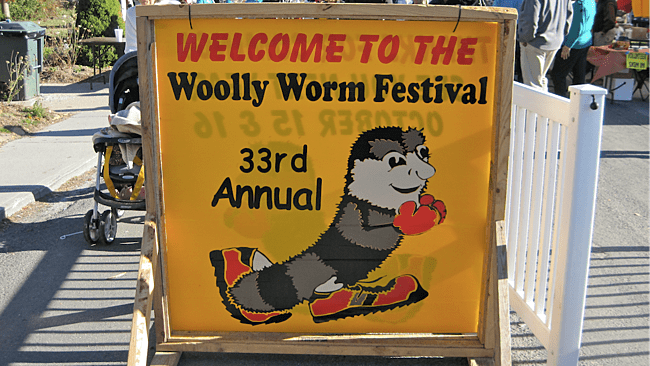

One of those fun things going on since 1978, is when residents of Elk Creek, North Carolina, have celebrated the coming of the snow season with the Woolly Worm Festival. They set aside the  third weekend in October to determine which one worm will have the honor of predicting the severity of the coming winter. That worm earns the honor by winning heat after heat of hard-fought races – up a three-foot length of string. In addition to winning the privilege of predicting the weather, the winning worm also receives a $1,000 prize. Adam Binder, co-organizer of the Woolly Worm Festival, said that the woolly worm has an 87 percent accuracy rate in its predictions. The Woolly Worm Festival is a prime attraction for the one-stoplight town of Banner Elk, drawing over 22,000 visitors annually. Sounds like something we should do locally.

third weekend in October to determine which one worm will have the honor of predicting the severity of the coming winter. That worm earns the honor by winning heat after heat of hard-fought races – up a three-foot length of string. In addition to winning the privilege of predicting the weather, the winning worm also receives a $1,000 prize. Adam Binder, co-organizer of the Woolly Worm Festival, said that the woolly worm has an 87 percent accuracy rate in its predictions. The Woolly Worm Festival is a prime attraction for the one-stoplight town of Banner Elk, drawing over 22,000 visitors annually. Sounds like something we should do locally.

So maybe, just maybe, the wooly worm can predict the winter to some degree. Hmm…maybe I need to find myself one of them. Feel free to comment on this post and be sure to hit the “Like” button at the end.